Human Geography Made Simple: Utopian Geographies

- Jonathan Warke

- Nov 11, 2021

- 3 min read

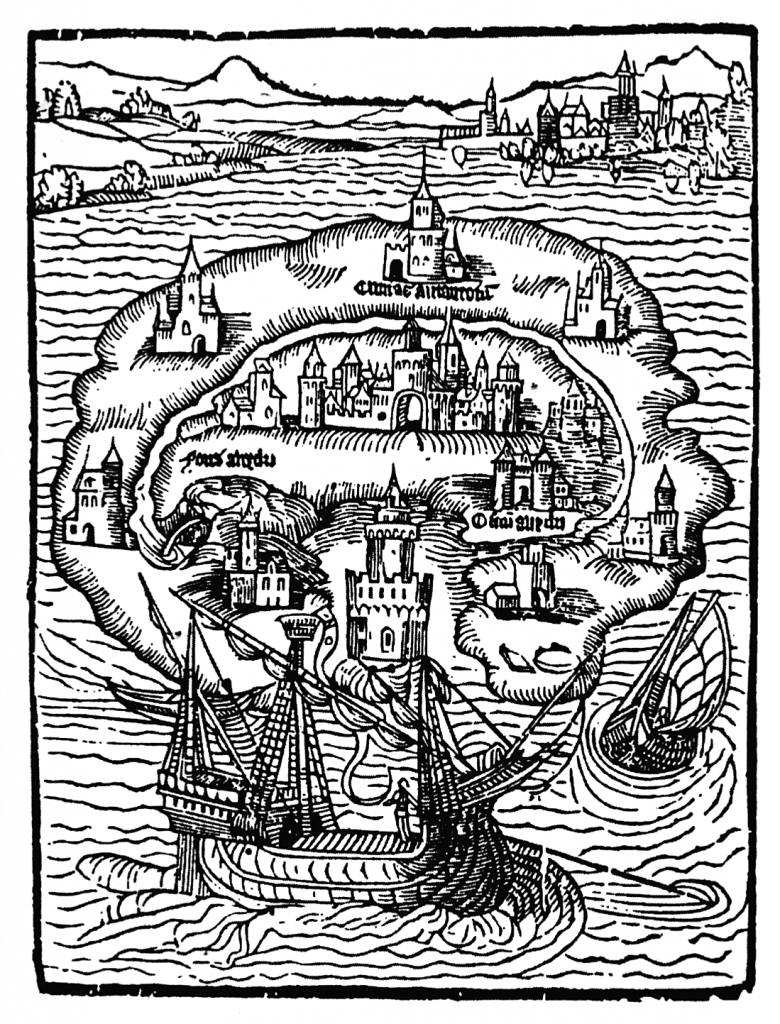

The idea of ‘utopia’ in geographical thinking was first explored by Thomas More (1516), in fact More coined the term ‘utopia’ (Vieira, 2010) when imagining a perfect island where both pristine beaches and flawless cities existed, as well as societal equality - of sorts. Influential to imaginative geography as More was, he didn’t create the notion of longing for a better world, only the more tangible expression of that longing. (Vieira, 2010) Utopia has since been defined as “an ideal society, state or commonwealth in which the problems of the present have been transcended” (Pinder, 2005). The depiction of utopian society and the search for it can be easily observed in literature and film. (Pinder, 2005) For example, the post-apocalyptic film “Mad Max: Fury Road” (2015) shows the journey of some fugitives in search of the “green place”, their utopia. Another allusion to the search for utopia in society and politics is the obvious human desire for change and reform that runs through much of history.

Utopia, despite being obviously conceptual, is grounded in a sense of place. David Harvey (2010) claims “social processes are spatial” and therefore it would be an oversight to examine the idea of ‘utopia’ without a geographical perspective. The sphere of ‘imaginative geographies’ comfortably includes utopian thinking within “representations of other places that articulate the desires, fantasies and fears of their authors and the grids of power between them and their ‘Others’” (Gregory, 2011), particularly in relation to “desires” and “fantasies”. Some scholars argue utopia is incredibly important to our understanding of the world; Oscar Wilde wrote “a map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at” (1891). However, there are a few prominent difficulties that arise with ‘utopia’. Firstly, when realised, utopianism rests deeply on authoritarianism and totalitarianism (Harvey, 2000), as participants in a utopian reality would be subjected to a singular and inflexible type of society or lifestyle. Another difficulty with utopia, connected to the first, is that one person’s utopia may not be the next person’s utopia; ‘one man’s heaven is another man’s hell’. (Goodwin, 1864) This is illustrated in More’s ‘Utopia’ (1516) - what he sees as a perfectly equal society still contains slavery in some form. It’s hard to imagine those in slavery would envisage their situation as utopia. Finally, “utopia’s of spatial form get perverted from their noble objectives by having to compromise with the social processes they are meant to control.” (Harvey, 2000) As David Harvey explains, utopia is intrinsically imaginative. Therefore as soon as utopia is realised spatially, it no longer holds the same “ideal character”. This impossibility of utopia is alluded to in “Mad Max: Fury Road” (2015) where the fugitives’ journey to “the green place” is in vain when they discover in reality it doesn’t exist. It seems true utopia is confined to imagination, and utopia in reality soon morphs into totalitarian dystopia. (Claeys, 2016)

Bibliography:

Claeys, G. (2016). Dystopia: a natural history. Oxford University Press.

Goodwin, T. (1864). The Works of Thomas Goodwin (Vol. 9). J. Nichol.

Gregory, D., Johnston, R., Pratt, G., Watts, M. and Whatmore, S. eds. (2011). The dictionary of human geography. John Wiley & Sons. pp.369-370

Harvey, D. and Harvey, F.D. (2000). Spaces of hope (Vol. 7). Univ of California Press. pp.156-181

Harvey, D. (2010). Social justice and the city (Vol. 1). University of Georgia Press. pp.11.

Mad Max: Fury Road. (2015). [DVD] Directed by G. Miller. Australia: Warner Bros.

More, T. (1516). Utopia. Yale University Press.

Pinder, David. (2005). ’Utopia’, in Gregory, D et al. (eds) Dictionary of Human Geography (Oxford: Blackwell): 795-796

Vieira, F. (2010). The concept of utopia. The Cambridge companion to utopian literature, pp.3-27.

Comments